Dưới đây là tựa đề và tóm tắt các bài viết về mua bán doanh nghiệp (M&A) của các tác giả khác mà Ngữ vô tình thấy được bắt đầu từ ngày hôm nay (26/3/2021) và sẽ được cập nhật dần theo thời gian. Nhiều bài Ngữ cũng chỉ đọc qua tóm tắt và đưa lên đây chứ chưa kịp đọc hết. Click tựa đề để tải trọn bài từ nguồn chính chủ. Trang này sẽ ngày càng dài nên hãy sử dụng chức năng tìm kiếm (Ctrl + F) keywords.

Cũng có thể tìm lại các bài viết ngắn gọn của Ngữ về M&A trên trang này trong Archive. Có thể tìm đọc sách & bài viết chính thức về M&A của Ngữ trên Chanhngu.vn. Có thể tham gia thảo luận về M&A trên page “Pháp Lý M&A Căn Bản”.

Còn trước hết dưới đây là phần giới thiệu về nguồn miễn phí để tìm hiểu căn bản về M&A.

Có thể tìm hiểu cơ bản, có hệ thống, một cách tiện lợi pháp luật về M&A của Mỹ từ nguồn sau đây:

Corporations in 100 Pages (Mergers and Acquisitions)

Corporations (Spamann, Harvard Opencasebook)

Documentation and Negotiation: The Merger Agreement (A chapter in Hill, Quinn, and Davidoff Solomon's Mergers and Acquisitions: Law, Theory, and Practice)

The Deal Lawyers’ Guide to Public and Private Company Acquisitions (M&A Institute co-chaired by H. Rodgin Cohen and my mentor, Prof. Samuel C. Thompson, Jr.)

Takeover Law and Practice 2020 (Wachtell Lipton)

Outline of Legal Aspects of Mergers and Acquisitions in the United States (Pillsbury, 2003)

Law Shelf (Business Law & Bankruptcy)

Blog & Website

Oxford Business Law Blog (M&A)

The Lipton Archive (and Memos)

Simplified Codes (and The Readable Delaware General Corporation Law 2021-2022)

Cross-Border M&A: A Checklist of US Issues for Non-US Acquirers (Clifford Chance)

Finding Merger and Acquisition Information (LexisNexis)

Edspira (Mergers and Acquisitions in Corporate Finance)

Investopedia (Mergers and Acquisitions)

Coursera (Mergers and Acquisitions – The Relentless Pursuit of Synergy)

Private mergers and acquisitions in the United States: overview (Shearman & Sterling on Practical Law)

USA: Mergers & Acquisitions Laws and Regulations 2021 (Skadden)

The Latham & Watkins Take-Private Guide: An overview of acquiring a US public company (2021)

Business Scholarship Podcast (Prof. Andrew K. Jennings)

Selling the company: A practical guide for directors and officers (DLA Piper)

A Guide to Takeovers in the United Kingdom 2021 (Slaughter & May)

UK’s Panel on Takeovers and Mergers [No newsletter function, apparently.]

Cross-Border M&A Resource Center (Baker & McKenzie)

Overview of Mergers and Acquisitions in Vietnam 2019 (Frasers)

Vietnam Business Law (Venture North Law)

Vietnamese Law Blog (Indochine Counsel)

The Mergers & Acquisitions Review: Vietnam (Nishimura & Asahi)

Corporate M&A 2021 (LNT & Partners)

M&A Report 2021 (YKVN)

Vietnam Investment Guide (Dilinh Legal, 2021)

Doing Business in Vietnam: Overview (Tilleke & Gibbins, 2021)

Corporate Valuation

What are the Main Valuation Methods? (Corporate Finance Institute)

Damodaran Online (Valuation)

Corporate Finance Institute (Valuation)

IPEV Valuation Guidelines (2018)

Selling your business in Vietnam for foreign investors (Acclime)

M&A: A Practical Guide to Doing the Deal (Paywalled, Wiley, 2nd Ed)

On merger control, see Antitrust (Competition Law) Chapter.

For Vietnam’s M&A activity in the news, see Vietnam M&A in the Spotlight.

(6/8/2022)

Locking the Box in Private M&A Transactions – Myths and Facts

Purchase price adjustment mechanisms are common in private M&A transactions to determine the final price to be paid by the buyer. However, the manner in which the price adjustment is achieved varies by jurisdiction. In the US, it is common to adjust the purchase price for cash, any excess or deficit of net working capital relative to a required level of net working capital, unpaid debt, and unpaid transaction expenses of the target business as of the closing, with an adjustment done at closing based on estimates and followed by a post-closing true-up. In the UK and Asia, what is commonly referred to as the “locked-box” approach is more frequently used, particularly in auction processes, corporate carve outs and private equity transactions.

(11/6/2022)

But the discount-on-a-discount analysis misconstrues materiality. Something is material if it would affect the buyer’s decision. That’s demonstrated by one of my definitions of material (taken from the manuscript of my article on the ambiguous material):

“Material” and “Materially” refer to a level of significance that would have affected the decision of a reasonable person in the Buyer’s position regarding whether to enter into this agreement or would affect the decision of a reasonable person in the Buyer’s position regarding whether to consummate the transaction contemplated by this agreement.

Here are the statement of fact and bringdown condition mocked up to reflect the significance of materiality on materiality, or rather the lack of significance:

Acme’s financial records contain no inaccuracies other than inaccuracies that wouldn’t reasonably be expected to change the Buyer’s mind.

that the statements of fact made by the Seller in article 2 were accurate on the date of this agreement and are accurate at Closing, except, in both cases, for inaccuracies that wouldn’t reasonably be expected to change the Buyer’s mind;

This oversimplification shows that if a statement of fact and the bringdown condition are both qualified by materiality, then instead of effecting a discount on a discount, they both look to the same external standard, which is a function of the effect on the buyer.

The effect would be the same if instead of using materially (or in all material respects, which means the same thing), you qualified the statement of fact, or the bringdown condition, or both, by material adverse change or material adverse effect.

The exception applies unless the inaccuracy results in an MAE. It doesn’t make sense to think in terms of an inaccuracy resulting in an MAE. Instead, if, say, a “financial statements comply with GAAP” statement of fact is found to have been inaccurate, the circumstances giving rise to that state of affairs—and not the inaccuracy itself—constitute an MAE.

(30/1/2022)

New Decree on Real Estate Business Issued (by Indochine Counsel)

The rules for transferring real estate projects are specified in Article 9 of Decree 02. Particularly, (i) Article 9.2 provides that investment projects that have obtained the approval of the investor (or chấp thuận nhà đầu tư in Vietnamese) or the Investment Registration Certificate (the “IRC”) in accordance with the Investment Law, the transfer shall be implemented according to regulations relating to investment; and (ii) the transfer of other real estate projects2 which are not specified under Article 9.2 shall be carried out in accordance with the LoReB and Decree 023 .

Another notable point is that compared to Decree 76, Article 9.1 of Decree 02 emphasizes a condition for the project to be transferred is that it is an “on schedule according to the approved project content”. This is a new condition which increases the requirements for real estate projects to be transferred. The previous regulations only required the project "to complete the corresponding technical infrastructure works according to the progress of the project stated in the approved project”.

Decree 76 also provides documents required and the procedures for transfer of part or entire of real estate project of which the investment decision is granted by the Prime Minister or the provincial people’s committee.

(13/12/2021)

This paper analyzes the relationship between the economic structure of a SPAC, its corporate governance, and judicial review of SPAC mergers (or "deSPACs"). The core challenge for SPAC governance is to address the inherently conflicting interest of a sponsor and public shareholders. SPACs respond to this conflict by holding proceeds of their IPOs in trust and by granting public shareholders a right to redeem their shares for a pro-rata portion of that trust. For the redemption right to be effective, however, a SPAC's board must provide shareholders with accurate and complete information regarding the merger. Doing so may conflict with the interests of the SPAC’s sponsor, which will profit substantially even in a deal that is bad for SPAC investors. The independence of a SPAC's board is thus necessary for a SPAC to be governed in the interest of shareholders. Unfortunately, SPAC directors often have financial ties to a sponsor and are compensated in ways that align their interests with those of the sponsor. Where this is true, and where SPAC shareholders file suits alleging a breach of the duties of loyalty and candor, a court should affirm that the board has a duty to provide shareholders with the information they need to exercise their redemption right, and review the conduct of the sponsor and the board under an entire fairness standard.

(21/11/2021)

Vietnam’s M&A activity is set for another robust year following 2020’s potent performance. In the first three quarters, deals with disclosed value totaled US$3 billion. With three months of dealmaking left in the pipeline, 2021 is on track to overtake 2020’s annual total of US$3.9 billion.

(19/10/2021)

We recently helped a tech company that was founded in Vietnam open a Singapore company to act as the holding company of the Vietnam entity. To do this we had to not only setup the company in Singapore, but then we had to create the paperwork for the Singapore company to become the sole investor in the Vietnamese company, creating a 100% foreign owned company in Vietnam. We did this for two reasons. One, the company in question is interested in foreign expansion in the midterm and believes that having a parent company in Singapore will simplify that process. And two, the foreign investor insisted that the FDI, and their share of the ownership of the entity, happen in Singapore rather than Vietnam.

While this is a boon for lawyers and corporate service companies, it has negative implications for the international perception of Vietnam. Vietnam is seen as a difficult jurisdiction in which to do business. There is a great deal of administrative paperwork and with each administrative approval required the possibility for graft and corruption is multiplied. This has also contributed to the fact that Vietnam has yet to have a company list on a foreign stock exchange (though companies like Vinfast and a few others are pursuing reverse mergers of SPAC transactions in the near future). Vietnam is simply seen as a difficult jurisdiction in which to base internationally minded companies.

(9/10/2021)

Historically, escrows have served as a classic deal protection mechanism in mergers and acquisitions (M&A) transactions. Recently, however, representations and warranties (R&W) insurance has emerged as an escrow alternative, offering seller-friendly terms and competitive premiums. Is there room for two products on the market? Is one better than the other? Bottom line, it all depends. In this article, we will explore some areas to consider when evaluating the optimal deal protection mechanism for your transaction.

(5/10/2021)

The new Law on Investment No. 61/2020/QH14 (“LOI 2020”) and Decree 31/2021/ND-CP (“Decree 31”) introduce substantial changes to the framework of M&A approval. The changes are lauded to provide clearer guidance for foreign investors, especially in terms of business sectors that are open to foreign investment. Still, coming with these changes are new issues that require close attention and careful handling by stakeholders. This newsletter gives a brief of the circumstances where M&A approval is legally required and certain potential issues awaiting prospective investors in each circumstance.

(2/10/2021)

For Whom Corporate Leaders Bargain

At the center of a fundamental and heated debate about corporate purpose, an increasingly influential “stakeholderism” view advocates giving corporate leaders the discretionary power to serve all stakeholders and not just shareholders. Supporters of stakeholderism argue that its application would address growing concerns about the impact of corporations on society and the environment. By contrast, critics of stakeholderism argue that corporate leaders should not be expected to use expanded discretion to benefit stakeholders. This Article presents novel empirical evidence that can contribute to resolving this key debate.

(23/9/2021)

Special Purpose Acquisition Companies (SPACs) are simply enterprises that raise money from the public with the intention of purchasing an existing business and become publicly-traded in the securities markets. If the SPAC is successful in raising money and the acquisition takes place, the target company takes the SPAC’s place on a stock exchange, in a transaction that resembles a public offering. Also known as “blank-check” or “reverse merger” companies, this process avoids many of the pitfalls of a traditional initial public offering.

(22/9/2021)

Earlier this year the SGX consulted on a proposed listing framework for special purpose acquisition companies (SPACs). In a response to the consultation - published at the start of September and available here (pdf) - the SGX has confirmed that it will implement its framework "broadly as proposed with some amendments to reflect comments made by respondents on matters of detail and to clarify the intent of some of the Mainboard Rules" (para. 2.3).

(9/9/2021)

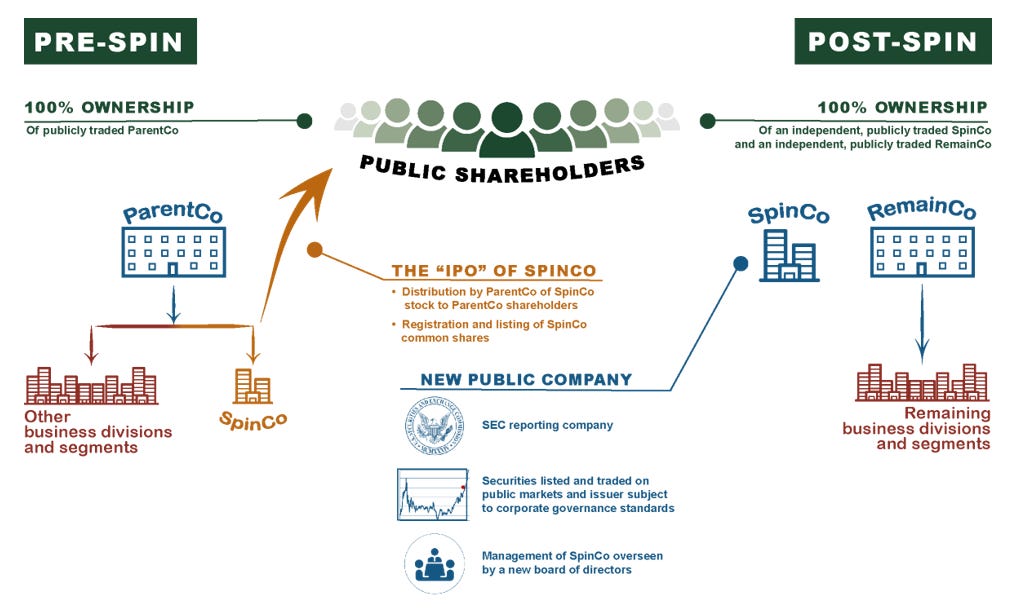

Spin-offs Unraveled (2019)

(3/9/2021)

Bàn về một số điểm mới của Luật đầu tư 2020 – Điều chỉnh giao dịch mua bán sáp nhập xuyên biên giới tại Việt Nam (Ths Trần Thu Yến)

Quotes one of my articles: “Luật Đầu tư 2020 và M&A.”

Những điểm mới về tổ chức lại doanh nghiệp theo Luật Doanh nghiệp năm 2020 (2020)

Luật Doanh nghiệp (LDN) năm 2020 có hiệu lực từ ngày 01/01/2021 đã có nhiều điểm mới mang tính đột phá, tạo điều kiện thuận lợi cho doanh nghiệp không chỉ trong việc thành lập mà cả quá trình hoạt động sản xuất kinh doanh. Một trong những điểm mới nổi bật trong LDN sửa đổi lần này là những thay đổi tích cực, thuận lợi hơn cho doanh nghiệp trong việc tổ chức lại doanh nghiệp.

For the last two decades, China has been the dominant story for both the global economy and capital markets, as the country's immense growth and infrastructure investments have sustained commodity prices, and altered the balance of world economic power. That growth has come (or should have come) with the recognition that in almost every venture in China, public or private, the Chinese government is not just a player, but often the key player determining the venture's success and failure. Afraid of being shut out of the biggest, growth market in the world, companies operating in China have accepted limits and constraints that they would fight in almost every other part of the world, including in their own domestic markets. That includes not just foreign companies, seeking to operate in China, but domestic companies, who, while benefiting from Beijing's backing, knew how quickly the iron fist could replace the velvet glove, in their dealings with the government. In the last year or so, Chinese tech companies, including shining stars like Alibaba, Tencent and Didi have also woken up to this recognition, and investors have had to readjust their expectations for these companies. In this post, I will begin by tracing out the rise of China to global economic power, and then focus on Chinese tech companies, with the intent of examining how government actions and inactions can affect value and pricing.

(01/9/2021)

This article argues that company takeover regulation regimes must carefully balance two opposing notions. On the one hand, the regime must be designed to enable or facilitate the initiation and successful implementation of takeovers and mergers in the interests of economic growth and technological advancement. On the other hand, such a regulatory framework ought to be sensitive to the ever-increasing need to protect national security interests, especially from veiled threats. These threats include cybercrimes, private data hacking and espionage, which are endemic to takeovers contemplated by foreign persons that possess technological sophistication and are leaders in the rapidly unfolding Fourth Industrial Revolution. Recently some jurisdictions, such as the United States of America and the United Kingdom, have been active in reforming their investment laws to particularly strengthen the protection of national security interests. Similarly, in South Africa the debut introduction of section 18A of the Competition Amendment Act 18 of 2018 has enabled the addition of a concurrent but parallel standard to the pre-existing merger control criteria prescribed under section 12A of the Competition Act 89 of 1998. This article evaluates the efficacy of South Africa's framework for national security interests' protection in the context of merger control using its US and UK counterparts as comparators. Ultimately, the article proposes reforming the existing statutory and institutional framework to effectively accommodate national security interests in South African merger control.

(30/8/2021)

Reforming State-Owned Enterprises in a Global Economy: The Case of Vietnam (2020) [A free book chapter from the generous Springer Link]

What does the new phase of SOE reforms starting around 2016 tell us about economic and institutional transformations and contradictions in Vietnam? In raising this question, we shed light on contradictions between the Vietnamese socialist ideology and the market imperative and international pressure the Vietnamese economy is subject to as a global player. In the wake of the doi moi process for economic renewal, the need of reforming the SOE sector attained a lot of attention. The Government decided to promote equitization of SOEs in 1992. This means that the enterprises should be turned into joint stock companies in which the state, workers and private investors hold shares, and that either the state or the private investors hold the majority shares. However, the process went slowly. There were considerable resistance from managers and a fear of job losses. What then characterizes the new phase of SOE reforms? What is new about the context that the reforms are implemented in? After a brief account of previous SOE reforms we delve into how the state and industry plan for, perceive and experience the new phase of reforms and how the reforms are addressed by international institutions and mass media.

(28/8/2021)

The amount of capital in sustainable investing funds has risen in recent years, as investors’ awareness towards Environmental Social and Corporate Governance (‘ESG’) heightened related issues. This phenomenon has happened both in specific markets, such as the US and Europe, as well as on a global scale.

While contemporaneous literature on debt financing in green finance is abundant, there is a dearth of coverage concerning equity financing. My recent article ‘Venture Capital in the Rise of Sustainable Investment’ fills this lacuna and analyses the roles that VC funds play in sustainable investing, how it works, what the loopholes are, and the ways forward from a legal perspective.

(25/8/2021)

China has recently asserted more control over private companies in that country. Now, the SEC is threatening to not approve new company listings for companies based in China and possible delist currently listed NYSE and Nasdaq companies based in China. Most Chinese companies do give direct ownership, but often use the variable interest entity structure (VIE). In a VIE, a shell company is created in a foreign jurisdiction like the Cayman Islands. The shell company has a claim on the profits and assets of the parent company, although whether the claim is enforceable is debatable. As a result, the investment is more like an investment in a company in the Cayman Islands. Since the SEC requires full and fair disclosure, the SEC feels this unusual corporate structure should come with more warnings.

(23/8/2021)

On 24 January 2019, a revised Singapore Code on Take-overs and Mergers (the Take-overs Code) was promulgated by the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) on the advice of the Securities Industry Council (the SIC).

The revisions are to ensure that takeover practices targeting at companies with the dual class share (DCS) structures are conducted in compliance with the principle of equal treatment of all shareholders. The key amendments are two-fold: (a) expanding the application of mandatory offer and its dispensation to target companies with the DCS structures. (b) clarifying the fair pricing norms for multiple classes of equity share capital of target companies with the DCS structures.

The revisions feature several new Notes implementing the mandatory offer rule in the complex context of listed companies of DCS structures. These additional Notes provide greater certainty to market participants and potential business transactions. They reaffirm the fundamental principle that all shareholders, controlling or minority, multiple votes or one vote, shall be given the equal and fair opportunity to access the extra premium paid for the private benefits of control.

This regulatory development manifests the policy preference towards a strong shareholder protection in Singapore. It has been positively accepted by the market for corporate control, as evidenced by respondents’ endorsement to the consultation paper. Such a regulatory update also projects transnational implications to other jurisdictions which have recently incorporated the DCS structure. For example, on 30 April 2018, the Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited (HKEX) added a new chapter to the Main Board Listing Rules for weighted voting rights listings. The Codes on Takeovers and Mergers and Share Buy-backs have yet to been amended in the HK. Given the affinity of takeover rules between Hong Kong and Singapore, the recent revisions of Singaporean Take-over Code will be a valuable reference for the future amendments to the HK Take-over Codes.

(14/8/2021)

On 2 July 2021, the Prime Minister issued Decision Decision No. 22/2021/QD-TTg ("Decision No. 22"), setting out new criteria for classifications of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) for the purposes of divestment and restructuring of the SOEs for 2021 to 2025. […]

The state will hold 100% ownership in SOEs engaging in 13 sectors that primarily focus on national defense and security.

The state will hold at least 65% ownership in seven sectors (including banking and finance), and from more than 50% to less than 65% ownership in another seven sectors (including air transportation).

(11/8/2021)

Corporations, law firms and investment banks all state that diversity matters. This Article shows that there is a chasm between discourse and action. For the most important decisions undertaken by companies—large merger and acquisition (M&A) transactions—a gender gap persists. This Article provides a holistic examination of the entire network of lead actors involved in M&A, revealing that women’s leadership opportunities continue to be vastly unequal. Using hand-collected data from 700 transactions, this Article reveals that thirty years after women began to account for almost half of all law students, gender parity in M&A leadership lags far behind. To illustrate, over a 7-year period, women make up on average 10.5% of lead legal advisors for buyers in M&A. Moreover, this Article documents the lack of transparency on leadership data for other players in M&A. This Article argues that understanding, documenting, and disclosing the gender gap in M&A leadership is critical for increasing accountability and for determining the solutions that may work to reduce such disparities.

(9/8/2021)

Buying new companies and selling to other companies often involves inherent human rights risks – meaning the risk of harm to people. Those risks are steadily on the rise, and there is no shortage of examples of M&A transactions that fail, or cost significantly more for a company in the long term, because of a lack of consideration of human rights issues.

These kinds of inherent human rights risks are leading companies to start to integrate consideration for human rights into their M&A processes. Yet little information is publicly available about how they are seeking to do so. Revising due diligence checklists and crafting template representations and warranties alone will not work.

There is no shortage of examples of M&A transactions that fail, or cost significantly more for a company in the long term, because of a lack of consideration of human rights issues.

(8/8/2021)

Risky business [Pouring money into Chinese VIEs.]

When investors purchase a stock, what they're doing is buying a percentage of the company. Right?

Wrong! At least when it comes to many of the Chinese companies listed on the Nasdaq and the New York Stock Exchange.

That's because Chinese companies use a structure called a variable interest entity, or VIE, in order to raise money from foreign investors.

What's a VIE? The structure uses two entities. The first is a shell company based somewhere outside China, usually the Cayman Islands. The second is a Chinese company that holds the licenses needed to do business in the country. The two entities are connected via a series of contracts.

When foreign investors buy shares in a company that uses a VIE, they're purchasing stock in the foreign shell company — not the business in China.

For example, when US investors buy shares in Chinese ride-hailing giant Didi, which went public in June on the New York Stock Exchange, what they're actually doing is buying stock in a Cayman Islands firm called Didi Global.

Didi Global doesn't own the business in China that connects riders to drivers. But it does have contracts in place that entitle its shareholders to the economic benefits produced by that business.

(6/8/2021)

In Dargamo Holdings Ltd v Avonwick Holdings Ltd [1] the English Court of Appeal has held that the doctrine of unjust enrichment could not be used to subvert the contractual allocation of risk in a Share Purchase Agreement (SPA).

This is a notable decision for what it says about the interaction between contract law and unjust enrichment (and the limits of the latter). It is also a salutary reminder to those involved in the negotiation of SPAs (and other commercial contracts): wherever possible, parties should expressly reflect the full terms of their agreement, including any associated common expectations or understandings about what the contract provides for, in an executed written document. In relation to SPAs in particular, that means ensuring that all of the assets (and any other consideration) that a party expects to receive in exchange for the price paid should be clearly set out in the contract.

(28/7/2021)

M&As have been used as one of the most preferable strategies for firm growth. However, the motivations for M&A have changed mainly because the nature of technologies is changing. Due to the complicated nature of the latest technologies such as IoT and AI, as well as their rapid pace of change, firms acquire innovative startups that already deal with the cutting-edge technologies like Googles acquisition of DeepMind or Facebooks purchase of WhatsApp. The implications of these M&As are two-fold. First, by acquiring firms with high-skilled experts, existing firms can save the time and costs necessary not only to educate workers lack of technological background but also to catch up with cutting-edge and promising businesses. Second, acquiring innovative firms with diverse technologies and services can attract more customers, meaning this could be the best strategy for existing digital platform firms seeking profit-maximization through innovation due to network effects. Therefore, it is a good option for firms to acquire innovative companies in order to achieve long-run growth based on continuous innova

(26/7/2021)

For years, the Vietnamese Government has looked for ways to reduce its direct ownership in key state companies and so to broaden private ownership. For many reasons, equitization and divestment have not yet occurred on schedule or as intended. Recently, slow progress in equitization and divestment of SOEs has been attributable to Covid 19--but Covid 19 is only a recent cause. More fundamental causes are overpricing of shares, reluctance of local management to act, and bureaucratic inertia. Schedules have been set, and deadlines missed. Most recently, many SOEs missed 2020 deadlines contained in Decision No. 26/2019/QD-TTg of Prime Minister and deadlines have been reset to 2021.

(23/7/2021)

The Divergent Designs of Mandatory Takeovers in Asia

Optimal takeover regulation aims to promote efficient changes of corporate control while curbing inefficient takeovers. Viewed from a comparative perspective, the Anglo-American prototypes spearhead not only the discourse but also the dissemination of takeover regulation globally. At the one end of the spectrum, the law in the United States (U.S.) follows the “market rule,” whereby transfers of corporate control benefit from a regulatory freehand. At the other end of the spectrum lies the “mandatory bid rule” (MBR), epitomized by takeover regulation in the United Kingdom (U.K.). Under the U.K.’s version of the MBR, an acquirer who acquires de facto control over a target must make a general offer to the remaining shareholders to acquire all of their shares at the same price it paid to acquire the controlling block. In this article, we aim to analyze how and why six significant Asian jurisdictions adopted the MBR and its variants. This is puzzling given that the jurisdictions display considerable divergence in terms of structural, legal, and institutional foundations, not only with their Anglo-American counterparts but also even among themselves.

(8/7/2021)

For the first time in Vietnam, the LOI 2020 introduces a market access “negative list”, which means foreign entities are afforded national treatment with regard to investment except in those sectors explicitly set out in the List of Restricted Sectors. This is a more permissive approach than previous iterations of Vietnam’s investment regulations, which followed a “positive list” approach, blocking market access except in listed sectors.

(7/7/2021)

UK: New edition (13th) of the Takeover Code published (Corporate Law and Governance)

The thirteenth edition of the UK Takeover Code has been published: see here or here (pdf). A summary of the changes made in the new edition can be found here (pdf).

With Chinese companies this sort of thing is generally called a “variable interest entity.” [VIE] You set up a company in the Cayman Islands that can be owned by anyone. The Caymans company enters into a series of contracts with the local Chinese company, giving it, not ownership, but certain carefully curated economic interests and control rights over the Chinese company. Then you list the Caymans company in the U.S., and people buy its stock, and they sort of pretend that they’re buying stock in the Chinese company — they sort of pretend that the Chinese company is a subsidiary of the Caymans holding company — even though really they’re only buying an empty shell that has certain contractual relationships with the Chinese company.

(1/7/2021)

MAE cases arising from the COVID-19 pandemic such as AB Stable and KCake have focused attention on the exceptions typically contained in the definition of the term “Material Adverse Effect.” That is, merger agreements typically define the (capitalized) term “Material Adverse Effect” to be any event that has or would reasonably be expected to have an (uncapitalized) material adverse effect on the target, other than certain excepted events such as general changes in business, market or industry conditions, changes in law, or force majeure events. The COVID-19 cases have exposed a latent ambiguity in this definition because, while the definition assumes that a single event causes a material adverse effect on the target, in the COVID-19 cases the causal background to the supposed material adverse effect was more complex, with one event (the pandemic) causing a second event (e.g., governmental lockdown orders) and the second event causing the material adverse effect on the target. If the MAE definition allocates the risk of both events to the same party, then clearly that party bears the risk of any resulting material adverse effect, but what happens if, say, the risk of a pandemic is allocated to the target but the risk of changes in law (such as lockdown orders) is allocated to the acquirer? Albeit only in dicta, AB Stable and KCake answered this question by saying, in effect, that if the risk of either event is allocated to the acquirer, there is no Material Adverse Effect. This article argues that this reasoning is unsound. The argument begins from the fundamental point that, under the express terms of the typical MAE definition, a (capitalized) Material Adverse Effect is an event that causes an (uncapitalized) material adverse effect; it is counterintuitive but plainly correct that a Material Adverse Effect is thus not a material adverse effect but an event that causes a material adverse effect. Furthermore, MAE definitions allocate risk on the basis of events, not effects, and they do so not because parties care about the events in and of themselves but because of the tendency of the events to cause material adverse effects. Hence, in allocating the risk of a certain event, the parties are allocating the risk not only of the event itself but also of all other events reasonably expected to follow from the event, up to and including any reasonably-expected material adverse effect on the target. This means, for example, that if the target bears the risk of a pandemic, it also bears the risk of everything reasonably expected to follow from any pandemic that occurs, including any reasonably-expected lockdown orders, up to and including any reasonably-expected material adverse effect, even if the MAE definition includes exceptions related to changes in law that would otherwise except lockdown orders. Even if the lockdown orders are mistakenly regarded as excepted, the pandemic was not excepted, and so if the pandemic would reasonably be expected to result in a material adverse effect (via lockdown orders or otherwise), then the pandemic is a Material Adverse Effect even if the lockdown orders (because they are excepted) are not. Courts have misunderstood this point because they have conflated Material Adverse Effects with material adverse effects and treated the exceptions in the MAE definition as if they applied to material adverse effects rather than to events causing material adverse effects. The article traces the origin of this confusion to one of the author’s own law review articles from 2009. Finally, the article discusses the import of the language introducing the exceptions in the MAE definition that sometimes expands the scope of the exceptions in various ways.

(27/6/2021)

The Divergent Designs of Mandatory Takeovers in Asia [Vietnam’s takeover rules are laid out in her securities laws, but I post this here as it is an essential aspect of M&A.]

Optimal takeover regulation aims to promote efficient changes of corporate control while curbing inefficient takeovers. Viewed from a comparative perspective, the Anglo-American prototypes spearhead not only the discourse but also the dissemination of takeover regulation globally. At the one end of the spectrum, the law in the United States (U.S.) follows the “market rule,” whereby transfers of corporate control benefit from a regulatory freehand. At the other end of the spectrum lies the “mandatory bid rule” (MBR), epitomized by takeover regulation in the United Kingdom (U.K.). Under the U.K.’s version of the MBR, an acquirer who acquires de facto control over a target must make a general offer to the remaining shareholders to acquire all of their shares at the same price it paid to acquire the controlling block.

In this article, we aim to analyze how and why six significant Asian jurisdictions [China, Japan, Korea, India, Singapore, and Hong Kong] adopted the MBR and its variants. This is puzzling given that the jurisdictions display considerable divergence in terms of structural, legal, and institutional foundations, not only with their Anglo-American counterparts but also even among themselves. In this article, we challenge the prevailing notion that the binary Anglo-American approach constitutes the framework for the dissemination of takeover regulation worldwide.

We claim that because of the political economy of takeover regulation in the Asian jurisdictions, the choice to adopt various intermediate positions is by design and not by default. Considering the market rule provides suboptimal protection to minority shareholders and the MBR curbs the market for corporate control, the intermediate positions aim to balance these somewhat conflicting objectives. Our study contributes to the wider debate surrounding the appropriate takeover regulation and, more specifically, the claims made by the proponents of the market rule on the one hand and the MBR on the other.

(13/6/2021)

The Rise of SPACs: IPO Disruptors or Blank Check Distortions? [See more on SPACs below)

For decades, the process that companies in the United States have used to go public has followed a familiar script. The company files a prospectus, providing prospective investors with information about its business model and financials, and hires an investment banker or bankers to manage the issuance process. The bankers, in addition to doing a roadshow where they market the company to investors, also price” the company for the offering, having tested out what investors are willing to pay, and guarantee that they will deliver that price, all in return for underwriting commissions. During the last decade, as that process revealed its weaknesses, many have questioned whether the services provided by banks merited the fees that they earned. Some have argued that direct listings, where companies dispense with bankers, and go directly to the market, serve the needs of investors and issuing companies much better, but the constraints on direct listings have made them unsuitable or unacceptable alternatives for many private companies. In the last three years, SPACs (special purpose acquisition companies) have given traditional IPOs a run for their money, and in this post, I look at whether they offer a better way to go public or are more of a stop on the road to a better way to go public.

(10/6/2021)

President Issues Executive Order Revoking TikTok and WeChat Executive Orders and Addressing Access by Foreign Adversaries to U.S. Personal Data [and sure, we can access a full version of the new order right here.]

On June 9, 2021, President Biden signed an Executive Order (the “Order”) that purports to address national security risks related to the increased use of certain connected software applications designed, developed, manufactured, or supplied by persons that are owned or controlled by a “foreign adversary,” which the Order defines as “any foreign government or foreign non-government person engaged in a long-term pattern or serious instances of conduct significantly adverse to the national security of the United States or security and safety of United States persons.” The Order affirms the national emergency measures provided in Executive Order 13873 of May 15, 2019 (“Securing the Information and Communications Technology and Services Supply Chain”) and revokes other related executive orders issued by the Trump Administration. Our prior client alert reporting on implementation of Executive Order 13873 is available here. The Order explains that the national emergency declared in Executive Order 13873 “arises from a variety of factors, including the continuing effort of foreign adversaries to steal or otherwise obtain United States persons’ data.”

The Order further explains that this continuing effort “constitutes an unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security, foreign policy, and economy of the United States,” and that the United States must protect against risks to personal data associated with a connected software application, which the Order defines as “ software, a software program, or a group of software programs, that is designed to be used on an end-point computing device and includes as an integral functionality, the ability to collect, process, or transmit data via the Internet.” The Order describes foreign adversary access to large repositories of U.S. personal data as posing “a significant risk.”

The Order also affirms that the U.S. Government seeks to promote accountability for serious human rights abuse. Specifically, the Order explains that the U.S. Government may impose consequences through separate action from this Order “if persons who own, control, or manage connected software applications engage in serious human rights abuse or otherwise facilitate such abuse.”

(9/6/2021)

Acquisition Flippers and Earnings Management [You will see colorful phrases like “buy it, strip it, flip it” and “window dressing”.]

Mergers and acquisitions are considered an integral part of a well-functioning governance system, an effective device for transferring corporate control to more capable owners and executives who can manage firm assets more efficiently and create economic value for shareholders of target firms. Acquirers, meanwhile, aim to reap financial synergies by integrating their economic resources and operations with those of targets. All this takes time, though, which is why mergers are often considered long-term corporate investments. Nonetheless, in about $3.5 trillion worth of deals, representing 23 percent of U.S. M&A activity from 1980 to 2015, targets were resold.[1] This phenomenon casts doubt on not only the effectiveness but also the intent of M&A….

Acquiring a firm to flip it is certainly different from acquiring a firm to own it long-term. As temporary owners, acquisition flippers focus on maximizing the sale prices of targets. While long-term value creation can increase sale prices, it is not feasible to enhance targets’ intrinsic value in a relatively short period of time. For acquisition flippers, a simple way to boost sale prices may be to make cosmetic improvements to earnings by, for example, manipulating accounting numbers to inflate the performance of newly acquired targets. Earnings that are merely window dressing, however, will probably not be sustainable. As indicated to us in a private conversation by an employee whose company was acquired and resold by an investment bank in less than three years, the subsequent acquirer (a private company) found it impossible to maintain the level of pre-acquisition earnings and had to undertake significant restructuring just to break even.

(1/6/2021)

This chapter examines how screening of foreign direct investments could take place through European company law. It scrutinizes the contribution of both CJEU’s case law and harmonization of European company law to an effective screening of foreign direct investments. On the basis of this approach, this chapter is divided into two parts. The first part focuses on CJEU’s case law and the second part examines harmonization. An examination of the freedom of establishment of companies in the light of CJEU’s case law on corporate mobility sheds light on screening of foreign direct investments. The impact of the privatizations of State-owned companies and of the CJEU’s golden shares case law on screening of foreign direct investments is discussed. This chapter analyses how certain harmonizing instruments of European company law could contribute to screening of foreign direct investments. The relationship between the goals of the harmonization of European company law and screening of foreign direct investments is also scrutinized. The Takeover Bids Directive with its optionality and reciprocity regime and with its requirements for disclosure of information could contribute to an effective screening of a foreign direct investment behind a takeover bid. Additionally, this chapter examines how the Shareholders Rights Directive II, the Transparency Directive, the Cross-border Mergers Directive (repealed and consolidated into Directive 2017/1132) and the European Company Statute (Societas Europaea-SE) could contribute to investment screening. Some concluding remarks are deduced on the importance and effectiveness of European company law for the screening of foreign direct investments.

(29/5/2021)

The flowchart is handy. Remember my introduction of CFIUS (Committee for Foreign Investment in the United States) to Vietnamese readers? Here it is: “Cách nước Mỹ xử lý giao dịch đầu tư ảnh hưởng an ninh quốc gia”.

Asia: Talent retention

Research has shown that culture is a top reason for deals failing to achieve their objectives. This is the number one issue we see in preparing for deal close in Asia. The talent market in many Asian countries is generally tight; adding in the disruption of an acquisition can squeeze this even further as employees take the opportunity to consider their career options. Willis Towers Watson’s Global M&A Retention Study found that, globally, 79% of acquirers using retention incentives retained at least 80% of targeted employees for the full retention period. In Japan, this was 100% of acquirers, but in China it was less than 40%. How should a buyer identify key talent for retention? Our data and experience overwhelmingly point to the target’s leadership team as the best source of information. From there, you must decide on the retention risk, award design and time period. More broadly, if you are acquiring through an asset deal, this is a red flag for retention. In many Asian countries, there is no automatic transfer of employment for an asset deal. In some countries, employees know they may be paid severance from the seller if they refuse to transfer. This puts the buyer in a difficult negotiating position if the employees have in-demand skills and can find a job easily elsewhere. Companies may have to budget for a transfer incentive close to the severance payout value to encourage a smooth transition of the workforce.

(25/5/2021)

What You Need to Know About SPACs (SEC) [Yeah, they’ve just sent this to my inbox.]

This bulletin provides a brief overview for investors of important concepts when considering investing in a SPAC [special purpose acquisition company], both (1) when the SPAC is in its shell company stage and (2) at the time of and following the initial business combination (i.e., when the SPAC acquires or merges with an operating company). It is important to understand how to evaluate an investment in a SPAC as it moves through these stages, including the financial interests and motivations of the SPAC sponsors and related persons.

Read also “Special Purpose Acquisition Companies: An Introduction” and “A Sober Look at SPACs”.

And did you know this: “VinFast adds banks to advise on U.S. listing, but plan faces delay -sources”? SPAC was also put in the spotlight in Vietnam just because of this kind of “plan”.

Reuters reported earlier in the month that VinFast was eyeing a valuation of about $60 billion and had appointed Credit Suisse to lead the potential transaction. Sources have said VinFast’s IPO could raise at least $2 billion, and one source had said a deal was slated for the second quarter. VinFast’s preferred scenario is to merge with a SPAC for a U.S. listing, said two sources who had direct knowledge of the matter. However, they said the talks with the SPACs haven’t made much headway in terms of coming up with deal proposals or a specific timeline for a listing. This was due to uncertainty surrounding SPAC regulations in the United States, said the sources, who did not want to be named as the information has not yet been made public. A time table on a transaction has not been set and the company’s plans could change, they added.

(22/5/2021)

MAE clauses in business combination agreements almost never define the phrase “material adverse effect,” and so the meaning of that key expression derives primarily from a line of Delaware cases starting with In re IBP Shareholders Litigation. In that case, the court said that a material adverse effect requires an event that substantially threatens the overall earnings potential of the target in a durationally-significant manner. In implementing this standard in IBP and subsequent cases, the courts have had to determine how the target’s earnings should be measured (e.g., by EBITDA or by some other measure of cashflow), how changes in earnings should be determined (e.g., which fiscal periods should be compared with which), and how large a diminution in earnings is material. Neither IBP nor subsequent cases have provided clear and convincing resolutions of these issues. On the contrary, later cases have introduced yet new problems, such as whether it matters that the risk that has materialized and adversely affected the target’s business was known to the acquirer at signing, whether material adverse effects should be measured in quantitative ways, qualitative ways, or both, and whether a material adverse effect must be felt by the company within a certain period of time after the occurrence of the event causing the effect. This article proposes a new understanding of material adverse effects that solves all of these problems. Beginning from the foundational premise that a material adverse effect should be understood from the perspective of a reasonable acquirer, this article argues that such an effect is a material reduction in the value of the company as reasonably understood in accordance with accepted principles of corporate finance—that is, as a material reduction in the present value of all the company’s future cashflows. Hence, to determine if there has been a material adverse effect, the court has to value the company twice, once as of the date of signing and again as of the date of the alleged material adverse effect, in each case much as it would in an appraisal action. Valuing the company is easier and more reliable in the MAE context than in the appraisal context, however, not only because the court need obtain only a range of values for the company at the two relevant times (and not pinpoint valuations as in appraisal proceedings) but also because it turns out that there is a canonical way to determine if a reduction in the value of the company would be material to a reasonable acquirer. The new theory of MAEs presented here solves all of the problems in the caselaw noted above and explains why those problems could not be solved with the conceptual resources available in the existing caselaw.

Reflecting on the past year, we believe that the key lesson of pandemic-era deal litigation has come from the Delaware Court of Chancery’s treatment of interim operating covenants. Recent rulings have provided more clarity on successfully showing a breach of interim operating covenants. They also emphasized the opportunity that parties have to build greater predictability into their agreements ex ante, by defining the conditions and relevant benchmarks for the seller’s interim conduct.

(19/5/2021)

Vietnam: New Rules for Foreign Investment in the Stock Market (by, my best friend, Mai Anh et al.)

In pursuit of the goal of improving the legal framework for investment and businesses, the government adopted Decree 155/2020/ND-CP on 31 December 2020 (“Decree 155”), which came into effect on 1 January 2021. Decree 155 introduces, among other things, new rules for foreign investment in the stock market. By these new rules, the government aims to promote foreign investment in the stock market while maintaining appropriate control over the inflow of foreign investment. This article highlights some of the key components of Decree 155.[…]

After being fiercely opposed by the banking industry, the proposal of the State Securities Commission (SSC) to take away the right of a public company to set its own foreign ownership cap (the “Foreign Cap”) has been set aside. Decree 155 goes further than its predecessor by now explicitly recognizing the right of a public company to set its own Foreign Cap, at its discretion, lower than the statutory Foreign Cap.[…]

Previously, an FIE was defined as an entity 51% or more of whose charter capital was held by foreign investors. Decree 155 now lowers the threshold to more than 50% (the “FIE Threshold”). This change means that (i) entities in which foreign investors hold more than 50% but less than 51% of the charter capital are now deemed to be FIEs and thus their investment will be captured by the rules on foreign investment control, and (ii) such new FIEs’ shareholding will be counted towards and cause a significant increase in the foreign ownership of public companies. Notably, investments by a subsidiary of an FIE are still not subject to the rule on foreign investment control.[…]

It is expected that this change will limit the number of shares in such companies that may be sold to foreign investors and FIEs, which suggests an end to the investment channel whereby foreign investors and FIEs could invest in non-voting shares, such as dividend preference shares, without any concerns about the Foreign Cap. However, NVDRs, as discussed below, may offer a suitable alternative for some foreign investors.[…]

Decree 155 appears to be a positive improvement to the foreign investment legal framework of Vietnam. Nevertheless, some uncertainties remain, such as enforcement and implementation of the remedies for excessive foreign investment as well as the regime for determination of FIEs status. Such kind of uncertainties will require further clarification and guidance from legislators.

Last Friday [April 30, 2021], soon-to-be Chancellor McCormick issued a decision in Snow Phipps Group, LLC v. KCake Acquisition, Inc. that ordered the defendant buyers to specifically perform their agreement to acquire DecoPac Holdings, Inc. (“DecoPac” or the Company), which sells cake decorations and technology for use in supermarket bakeries. The 125-page decision, which opens with a quote from the incomparable Julia Child (“A party without cake is just a meeting”), and is rightly described by the Court as a “victory for deal certainty,” offers a detailed analysis of several common contractual provisions in the time of COVID-19. Despite its length, it is a must-read for those interested in the drafting and negotiation of M&A agreements generally, and their operation during the COVID-19 pandemic specifically.

See also Have Your Cake, and Closing Too: Invoking Prevention Doctrine, Delaware Chancery Court Grants Seller’s Request for Specific Performance in COVID-Related M&A Dispute and Delaware M&A Opinion Rejects MAE Claim of COVID-19 Effects

Factors Affecting the Liquidity of Firms After Mergers and Acquisitions: A Case Study of Commercial Banks in Vietnam (by Thi Nguyet Dung NGUYEN, Thanh Cong HA, Manh Cuong NGUYEN)

The purpose of the research is to assess the factors affecting the liquidity of the commercial banks that are conducting mergers and acquisitions activities in Vietnam during the 2008–2018 period…The results shown that: (i) bank liquidity is positively affected by liquidity lagged, the return on equity (ROE) and economic growth; negatively affected by bank size, non-performing loan, short-run loan to deposit ratio; (ii) there is not enough evidence to conclude about the relationship between net profit margin, equity-to-assets ratio and inflation rate to bank liquidity; (iii) notably, we found evidence that, after the mergers and acquisitions, the liquidity of Vietnamese commercial banks decreased. The findings of this study suggest that bank managers take a more comprehensive view of the results of mergers and acquisitions and implications for banks to improve liquidity in the post-merger and acquisitions conditions.

(18/5/2021)

In brief: real estate acquisitions and leases in Vietnam (LNT & Partners) [See also my note on a related topic here.]

Foreign investors may acquire land use rights via land lease from the Vietnamese authorities or industrial park developers, or by way of capital contribution from local partners. When leasing land from Vietnamese authorities, foreign investors may elect to pay rent annually or once for the entire lease duration. In the case of annual rental payment, the rent may be reviewed from time to time by the local authority and the land users may be subjected to restricted land use rights (eg, cannot transfer to others if not approved by local authority). In the case of a one-time payment of rent for the entire lease duration, the land user has the same land use rights as local land users do. With land use rights contributed by local partners, the to-be-formed entity is entitled to the land use rights granted to the local partner.

The paper offers a comparative perspective on the duty of loyalty – encompassing both rules that govern self-dealing and corporate opportunity transactions. It compares the evolution of these two sets of rules in several European jurisdictions and in US Delaware law. Corradi and Helleringer note tensions between the evolution of the law governing self-dealing transactions at the European level, and the lack of harmonization on rules addressing corporate opportunities and continuing divergences in corporate opportunities doctrine across EU jurisdictions. They observe a relaxation of the duty of loyalty in US Delaware law, while there is an asymmetric evolution of its two components, self-dealing and corporate opportunities, in the European context. On the one hand, self-dealing rules have existed in European corporate laws for a long time and have been substantially relaxed in Europe in recent times as they have in the US. On the other hand, corporate opportunities rules have been introduced in most European jurisdictions only throughout the last two decades – without an express possibility of a waiver such as the one granted by DGCL s. 122(17).

The Rule of Law in the U.S.-China Tech War (including a section entitled “The United States Expands its National Security Regime” aimed at a brief discussion on CFIUS.]

U.S. policy is increasingly being influenced by suspicion of links between Chinese companies and the Chinese party-state and military. Competition over the technological future between the world’s two largest economies has produced a legal thicket of statutes, regulations, and executive orders in areas including foreign investment, data storage and privacy, and access to the U.S. capital markets. These regimes were created or bolstered due to legitimate concerns about the geo-economic impact of transactions that implicate control over advanced technology and data. Yet regulatory uncertainty engendered by the legal landscape has greatly complicated many aspects of the prosaic but fundamental work of producing innovative companies and technologies: cross-border investment and data flow, mergers and acquisitions, and talent recruitment. In this chapter, we approach the big policy issues in the U.S.-China tech war from the ground up, by exploring how the legal regimes recently developed in both countries to wage the tech war and operationalize technological decoupling affect cross-border deal making and domestic innovation. We fear that ironically, the rule of law necessary to maintain continued vibrancy in U.S. high-tech sectors is being compromised by some of the very actions ostensibly taken to protect these sectors from malign foreign influence. We conclude by offering some concrete policy suggestions to improve the transparency and effectiveness of national security and data protection regimes in the U.S. while advancing a second crucial objective – maintaining a regulatory environment conducive to technological innovation.

(11/4/2021)

The black letter law says that money damages are the preferred remedy for contract breach under US law. Specific performance is reserved for extraordinary circumstances. Contract theory tells us that default rules generally reflect what a majority of contracting parties would agree to, had they considered the matter. But do contracting parties agree with the law’s preference for money damages over specific performance? In a data set of more than 1000 M&A contracts, we find that in over 80% of transactions, parties choose specific performance as their preferred remedy. Using interviews with senior M&A lawyers we seek to unpack the reasons why parties are contracting around the law’s distaste for specific performance and default rule of money damages.

(04/04/2021)

Transactional planners heavily negotiate the provisions that govern the behavior of the parties during [the period between signing and closing in M&A transactions], not only to allocate risk between the buyer and seller, but also to manage moral hazard, opportunistic behavior, and other distortions in incentives….This Article is the first to examine the interaction between the MAE clause and the ordinary course covenant in M&A deals. We construct a new database of 1,300 M&A transactions along with their MAE and ordinary course covenants—by far the most comprehensive, accurate, and detailed database of such deal terms that currently exists. We document how these deal terms currently appear in M&A transactions, including the sharp rise in “pandemic” carveouts from the MAE clause since the COVID-19 pandemic began. We then provide implications for corporate boards, the Delaware courts, and transactional planners. Our empirical findings and recommendations are relevant not just for the next pandemic or “Act of God” event, but also the next (inevitable) downturn in the economy more generally.

(03/4/2021)

Corporate insiders’ trading activities are often used as a way to sign various potential firm-level events (e.g., dividend policy changes, seasoned equity offerings, open market share repurchases, corporate disclosures, etc.) as good or bad. However, it is not ex ante [based on forecasts rather than actual results] clear whether target insider trading can be used to infer the success of future M&As because the informational implications of target insider trading for acquisition outcomes are quite different from those of insider trading for the outcomes of other corporate events. In particular, prior to M&As, (1) target insiders are often uncertain about the bidder’s synergy potential, sometimes even lacking the knowledge of a potential acquisition, and (2) the Short Swing rule (i.e., SEC rule Section 16b), which requires any profits earned by insiders on round trip trades within any six-month period to be paid back to the firm, curbs target insiders’ trading prior to takeovers more severely than insider trading prior to other corporate events because takeover completion forces the sale of the target stock. […] Suppose target insiders have some private information that can be used by the acquirer to infer the target firm’s potential for generating acquisition benefits, whether or not target insiders are aware of a potential acquisition. Prior to takeovers, the Short Swing rule mainly discourages target insider trades pursuing short-term profits, so that target insider trades are more likely to pursue long-term profits and thus contain a signal that reveals target insiders’ private information on their firms’ long-term prospect. Under such circumstances, target insiders’ pre-M&A trades can be used by the acquirer as an information source in inferring the target’s potential for generating acquisition gains and synergies, regardless of whether target insiders intend to reveal targets’ synergy potential. We examine this “signaling” or “informativeness” hypothesis and find that the observable equity transactions undertaken by target insiders prior to M&As help acquirers make more efficient acquisitions.

(02/4/2021)

The Frustration doctrine of contract law excuses a party from its contractual obligations when an extraordinary event completely undermines the principal purpose of making the deal. This doctrine has long been a marginal player in contract litigation, as parties rarely invoked it—and usually lost when they did. The COVID-19 pandemic, however, is precisely the type of extraordinary event that Frustration was designed to address, and the courts have been inundated over the past year by a wave of colorable Frustration claims. This timely Article describes the Frustration doctrine and explores its application to the countless contracts whose purpose was undercut by the pandemic, such as leases for restaurant spaces in cities that banned dining service. The caselaw that develops out of the COVID-19 pandemic will define the Frustration doctrine for the next fifty years, and this Article provides an early assessment of the reported cases. Similarly, the Material Adverse Change (MAC) clause, a standard term in corporate acquisitions, allows a buyer to back out of a deal if the target company suffers a ‘material adverse change’ between signing and closing. In prior work, the present author argued that the MAC clause should be understood as a liberalized version of the Frustration doctrine, and this claim was adopted in the first Delaware case to find that a MAC had occurred, Akorn v. Fresenius. Like Frustration claims, MAC clauses have rarely been litigated, and claimants were almost universally unsuccessful. The COVID-19 pandemic, combined with the Akorn precedent, has led to numerous high-profile MAC claims, including one against jeweler Tiffany & Co. As with Frustration, the present wave of MAC litigation will establish the standards for MAC claims for years to come. This Article accordingly examines the merits of MAC claims premised on COVID-19 and reports on the one case decided to date.

(30/3/2021)

This study tests the strategic market-entry hypothesis by examining the acquisition location decisions (domestic vs. cross-border) of acquirers in the Vietnamese mergers and acquisitions market through the lens of corporate governance quality. Using a comprehensive dataset of target firms listed on Vietnamese exchanges, this study finds that cross-border firms prefer target firms with good corporate governance that enable them to quickly adapt to markets and reduce information asymmetry and differences of accounting practices, cultures, and legal frameworks. This result supports the view that cross-border acquisitions provide a method of strategic entry into foreign markets.

(29/3/2021)

A Black Swan Event? Implications of COVID-19 for Damages and Valuations in International Arbitration

(See certain notable points here)

Conventional wisdom portrays contracts as static distillations of parties’ shared intent at some discrete point in time. In reality, however, contract terms evolve in response to their environments, including new laws, legal interpretations, and economic shocks. […] This paper advances such a theory, in which the evolution of contract terms is a byproduct of several key features [dynamics of real-world contracting practice], including efficiency concerns, information, and sequential learning by attorneys who negotiate several deals over time. […] Using a formal model of bargaining in a sequence of similar transactions, we demonstrate how different evolutionary patterns can manifest over time, in both desirable and undesirable directions. We then take these insights to real-world dataset of over 2,000 merger agreements negotiated over the last two decades, tracking the adoption of several contractual clauses, including pandemic-related terms, #MeToo provisions, CFIUS conditions, and reverse termination fees.

(28/3/2021)

The traditional framework of U.S. private law that every first-year student learns is that contracts and torts are different realms: contracts is the realm of strict liability and tort, of fault. Contracts, we learn from the writings of Holmes and Posner, are best viewed as options: they give parties the option to perform or pay damages. The question we ask is whether, in the real world, that is indeed how contracting parties view things. Using a dataset made up of a thousand M&A contracts and thirty in-depth interviews with M&A lawyers, we find that there is at least one significant area of transactional practice that rejects the “fault is irrelevant to contract breach” perspective.

See also Prof. Brian JM Quinn’s ‘Response to The Cost of Guilty Breach: What Work Is “Willful Breach” Doing?’

(26/3/2021)

This 15th edition provides an insight into cross-border mergers and acquisitions laws, covering hot topics in the space. The opening expert analysis chapters delve further into the global M&A trends in 2020, as well as the M&A lessons from the COVID crisis. [Vietnamese law is not covered yet.]

This paper comprehensively reviews the empirical literature and the several confusing puzzles it raises, and works through the policy implications for the bodies of law it affects. The most important insights are two. First, the evidence casts doubt on the general confidence within corporations scholarship in the promise of oversight by robust market institutions, as an alternative to law and courts, especially the disciplinary power of the market for corporate control. Second, the less for antitrust law is simple.

While parties to large purchase or merger transactions typically include Material Adverse Effect (MAE) clauses in their agreements, there is little by way of detailed parameters in the law for what establishes such a material adverse effect. The clause can be used in various contexts but, in general, its purpose is to shift certain risks between the parties, providing buyers with a mechanism to avoid closing on a transaction if there is a significant enough change in the business of the target or underlying assets.